Standard 11: Family contact (2020)

Standard 11:

Every prisoner is encouraged and facilitated to maintain positive family and close significant relationships.

Rationale:

Children and families affected by imprisonment are often referred to as the ‘hidden’ or ‘forgotten’ victims of crime. While families and children have committed no crime themselves, they are punished indirectly for the actions of their parent or family member. Children have the right to maintain regular and direct contact with their parent. Every member of the family maintains a right to family life. Maintaining positive family contact is also a crucial factor in the rehabilitation and desistance process.

Current context:

Children’s rights, in particular the right to direct contact with their parents, as outlined under the UN Convention on the Rights of the Child,[255] have been significantly impacted by the Covid-19 pandemic.

Family visits were suspended from March until July 2020, when prison visiting re-commenced on a phased basis.[256] (This was later than other residential settings, where visits generally recommenced from end June.[257]) Initially only one adult was permitted to visit their family member. From 17 August 2020, a maximum of one child was allowed to visit a parent/family member in prison.[258] The plight of families, in particular having to choose only one child in the family to bring to visit their parent in prison – after 5 months without any physical contact - was documented in a survey conducted by IPRT.[259] From end August 2020, the reintroduction of local and national restrictions in response to infection rates in the community saw further suspension of visits at county and national level.[260] By 6 October 2020, in-person prison visits were again suspended across the country.[261]

While data on prison visits is not published on an annual basis, in 2018 there were 239,769 visitors to the prison estate of whom 50,592 were children.[262] In the first four months of 2019, there were 78,423 visitors to prisons of whom 16,207 were children.[263] These figures provide an estimate of the scale of visits affected by the restrictive measures imposed during the lockdown.

In the UK, legal action is being taken by a mother concerning her child’s lack of access to their father during the pandemic. The mother’s lawyers are arguing that a ban on visits and problems with video calls are a breach of children’s rights.[264]

In Ireland, a High Court challenge is also being brought over the reduction in prison visits.[265]

A number of positive measures were introduced by the Irish Prison Service in an effort to maintain family contact during the pandemic period. This included the roll-out of video calls as a substitute for visits to prisons.[266] The use of digital technology is particularly important for prisoners whose families may have never been able to visit, for example foreign prisoners whose families live abroad, and those with elderly relatives.

In a snapshot survey carried out by IPRT, 71% of respondents said they had issues with using ‘alternatives forms of contact’ including video calls.[267] Reasons cited for this included both financial and technical difficulties.[268] The Irish Prison Service responded to these issues by providing information sheets and a telephone helpline for families. The Irish Prison Service has been proactive in its communications throughout the pandemic, including assurance for friends and families around local outbreaks of Covid-19, and this is welcome.

Other positive developments included the installation of phones in cells in Cork Prison. Prisoners quarantining and isolating across the estate also had access to in-cell telephones.[269]

As restrictive measures associated with Covid-19 continue to prevail, the right to family contact and a child’s direct contact with their parent in prison requires scrutiny by the Government. In the UK, arising from an inquiry into the implications for human rights of the Government’s Covid-19 response, the Joint Committee on Human Rights concluded that the right to privacy for both mothers in prison and their dependent children risks being breached.[270] The Committee recommended:

“In order to comply with Article 8 of the ECHR, they must ensure that any restriction on visiting rights is necessary and proportionate in each individual case. Children must be allowed to visit their mothers in prison on a socially distanced basis, where it is safe for them to do so.” [271]

More generally, there were no reported national policy or legislative developments to support children and families affected by imprisonment from late 2019 to early 2020.

Indicators for Standard:

Indicators for Standard 11

Indicator S11.2: Regular family contact, specifically via phone calls, video conferencing and contact visits.

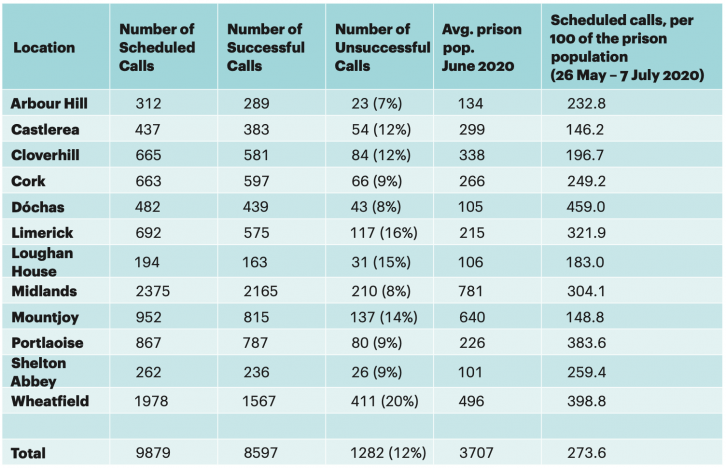

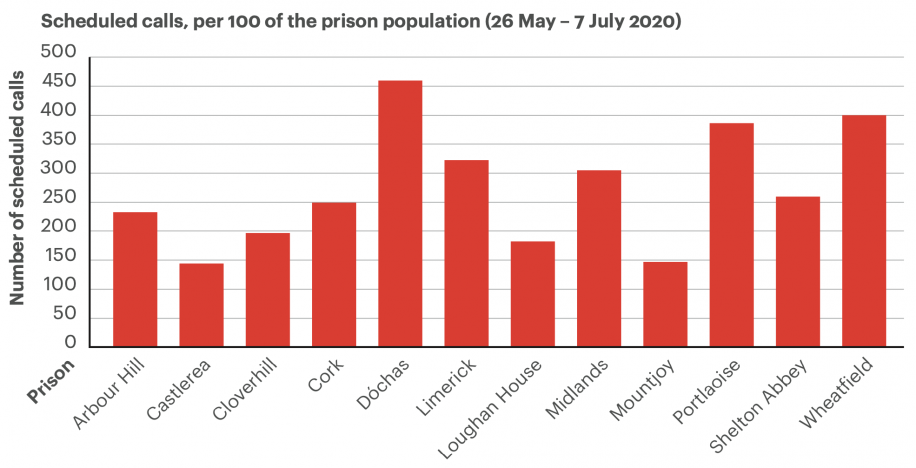

The table below provides a snapshot of the use of video calls by prison from 26 May 2020 to 7 July 2020 with an 87% success rate.[272] The use of video calls has expanded considerably in response to the pandemic; a total of 227 prisoner video calls took place between August 2018 and July 2019.[273]

The data shows inconsistencies across the prison estate in the use of video calls, for example, one-fifth of phone calls were unsuccessful from Wheatfield Prison and there were a disproportionately low number of scheduled calls in Mountjoy Prison, considering its large population.

Progressive Practice:

Progressive Practice, In-Cell Telephones

In an evaluation of digital technology in prisons carried out by the Ministry of Justice in England and Wales, in-cell telephones were seen as contributing to prisoners’ relationships with families outside the prison, particularly those with young children. Prisoners reported having more privacy and time to make calls. The overarching view was that the introduction of digital technology, in particular, in-cell telephones had contributed to an improvement in the psychological well-being of prisoners.[274]

HM Inspectorate of Prisons in England and Wales has welcomed the gradual roll-out of in-cell telephone provision as well as electronic kiosks, which makes it easier for prisoners to arrange healthcare appointments, visits and make complaints.[275]

In Cell Phone Provision and Video-Calls in Irish Prisons

A positive development has been in-cell phone provision. The main women’s prison, Dóchas Centre, was the first prison in the country to have phones in cells to allow for continued family support throughout Covid-19.[276] Feedback to this development has been very positive.[277] In IPRT’s small-scale survey, providing in-cell telephones was rated by family members as the most helpful measure to support family contact while restrictions were imposed.[278] The importance of video visits for family members was also highlighted in IPRT’s survey.

Actions required:

Status of Standard 11: Mixed

Rationale for Assessment

The impact of Covid-19 restrictions has been particularly harsh for children and families of prisoners. During the initial lockdown, these restrictions were considered necessary and in the interests of public health. However, further scrutiny by Government is required to ensure that current restrictions are proportionate and meet the rights of prisoners, families, and their children. IPRT welcomes the roll-out of video calls across the prison estate and increased in-cell phone provision. These measures should be seen as additional means to strengthen family contact in the future, not as a replacement for in-person prison visits.

| Action 11.1: |

The Irish Prison Service should expand in-cell phone provision across the prison estate to facilitate and strengthen family contact. |

|---|---|

| Action 11.2: |

The Irish Prison Service should retain virtual visits as a supplement to physical visits in future in order to promote and facilitate family contact post-pandemic. |

| Action 11.3: |

Government should scrutinise the necessity and proportionality of blanket restrictions on in-person visits between children and their parents in prison through a human rights lens. |

References:

-

255.

^

Article 9 (3) of the Convention on the Rights of the Child, https://www.ohchr.org/en/professionalinterest/pages/crc.aspx

-

256.

^

Irish Prison Service, Irish Prison Service Announcement on Recommencement of Physical Family Visiting, https://www.irishprisons.ie/irish-prison-service-announcement-recommencement-physical-family-prison-visiting/

-

257.

^

Government of Ireland, Roadmap for Reopening Society and Business, https://www.gov.ie/en/press-release/e5e599- government-publishes-roadmap-to-ease-covid-19-restrictions-and-reope/#phase-3-29-june

-

258.

^

Irish Prison Service, Irish Prison Service Announcement on Recommencement of Physical Family Visiting, https://www.irishprisons.ie/irish-prison-service-announcement-recommencement-physical-family-prison-visiting/

-

259.

^

IPRT Survey (2020) The experiences of people with a family member in prison during Covid-19. https://www.iprt.ie/covid-19- in-prisons/i-am-worried-about-the-lasting-impact-this-will-have-the-experiences-of-people-with-a-family-member-in-prisonduring-covid-19/

-

260.

^

Irish Prison Service, Important Notice – Physical Visits Suspended in Portlaoise and Midlands Prisons - August 7th, 2020, https://www.irishprisons.ie/important-notice-physical-visits-suspended-portlaoise-midlands-prison/

-

261.

^

Irish Prison Service, Suspension of Physical Visits to all Prisons, 6 October 2020, https://www.irishprisons.ie/suspension-physical-visits-prisons-06-october-2020/

-

262.

^

Houses of the Oireachtas, Prison Visiting Regulations, 16 May 2019, https://www.oireachtas.ie/en/debates/question/2019-05-16/27/

-

263.

^

Ibid.

-

264.

^

The Guardian, Mother sues MoJ over child’s lack of access to father in jails lockdown, https://www.theguardian.com/society/2020/aug/31/mother-sues-moj-over-childs-lack-of-access-to-father-in-jails-lockdown

-

265.

^

The Irish Times, High Court challenge brought over reduction of prisoner visits due to Covid-19, https://www.irishtimes.com/ news/crime-and-law/high-court-challenge-brought-over-reduction-of-prisoner-visits-due-to-covid-19-1.4366884

-

266.

^

Irish Prison Service, Important notice regarding the introduction of family video visits in Irish Prisons. https://www.irishprisons.ie/ wp-content/uploads/documents_pdf/Important-notice-regarding-the-introduction-of-family-video-visits-in-Irish-Prisons.pdf

-

267.

^

IPRT Survey (2020) The experiences of people with a family member in prison during Covid-19. https://www.iprt.ie/covid-19-in-prisons/i-am-worried-about-the-lasting-impact-this-will-have-the-experiences-of-people-with-afamily-member-in-prison-during-covid-19/

-

268.

^

Ibid.

-

269.

^

Irish Prison Service, Irish Prison Service response to requests for PIPS 2020 07.08.2020

-

270.

^

Joint Committee on Human Rights, Human Rights and the Government’s response to Covid-19: children whose mothers are in prison, https://publications.parliament.uk/pa/jt5801/jtselect/jtrights/518/518.pdf

-

271.

^

Ibid , p.15.

-

272.

^

Kildare Street, Written answers, Tuesday 14th of July 2020, Department of Justice and Equality, Prisoner Data, https://www.kildarestreet.com/wrans/?id=2020-07-14a.2592

-

273.

^

See Indicator 11.2 under PIPS Standard 11 Family Contact, https://pips.iprt.ie/progress-in-the-penal-system-pips/part-2- measuring-progress-against-the-standards/b-prison-conditions/11-family-contact/

-

274.

^

Palmer, M., RM Hatcher & M.Tonkin (2020) Evaluation of digital technology in prisons, p.5 https://assets.publishing.service.gov. uk/government/uploads/system/uploads/attachment_data/file/899942/evaluation-digital-technology-prisons-report.PDF

-

275.

^

HM Inspectorate of Prisons, HM Chief Inspector of Prisons for England and Wales Annual Report 2018–19, p.11 https://assets. publishing.service.gov.uk/government/uploads/system/uploads/attachment_data/file/814689/hmip-annual-report-2018-19.pdf

-

276.

^

Irish Prison Service, Irish Prison Service response to requests for PIPS 2020 07.08.2020

-

277.

^

Ibid.

-

278.

^

IPRT Survey (2020) The experiences of people with a family member in prison during Covid-19. https://www.iprt.ie/covid-19- in-prisons/i-am-worried-about-the-lasting-impact-this-will-have-the-experiences-of-people-with-a-family-member-in-prisonduring-covid-19/