Standard 12: Access to healthcare services (2020)

Standard 12:

The healthcare needs of individual prisoners are met. Every prisoner has access to healthcare that goes beyond the ‘equivalence of care’ principle, with a full range of preventative services and continuity of healthcare from and into the community.

Rationale:

The right to healthcare in prison is equal to that enjoyed by the general population. This is laid out in the Mandela Rules, the Bangkok Rules, and the European Prison Rules. The healthcare needs of the prison population are in fact higher than those of the general population. These needs must be met, particularly because of the lack of autonomy prisoners face in access and choice of healthcare. Imprisonment takes away an individual’s liberty but not their right to healthcare.

Current context:

In 2019, an independent prison health needs assessment was commenced[330] in line with recommendations made by the CPT[331] in 2011and 2015 on the need for a whole system review of healthcare in prisons and by the Inspector of Prisons in 2016.[332] The independent review aims to determine future health service requirements, while also considering the views of prisoners and their families. A number of prison visits as part of the assessment had taken place in February 2020.[333] However, due to Covid-19 restrictions, the project has had to be adapted. The review is expected to establish the current levels of service provision. The final report is expected to be completed by the end of 2020.[334]

Covid-19 response

The Irish Prison Service established an Emergency Response Planning Team (ERPT) with expertise in a number of areas including: operations, healthcare and infection control. The purpose of the ERPT was to prevent the spread of Covid-19 into a prison setting.[335] The IPS Executive Clinical Lead was appointed to the National Public Health Emergency Team (NPHET) Vulnerable Persons Subgroup.[336] This action demonstrates the joint approach between prison health and public health during the pandemic.

The Irish Prison Service followed guidance of the World Health Organisation and has received national and international praise for how it managed its response to Covid-19. A paper on its contract tracing system was submitted to the World Health Organisation as a model of best practice.[337] It highlighted the benefits of the collaborative approach taken by the Irish Prison Service and the Health Service Executive, which led to the rapid creation of in-prison contact tracing teams in every prison.

Records show that 212 prisoners were tested for Covid-19 between 6 April 2020 and 6 August 2020.[338] There were no confirmed cases among the prison population until the end of August 2020.[339] Following this, there were a small number of individual cases confirmed among the prison population in Dóchas, Cloverhill, and Limerick prisons and a contained outbreak in Midlands Prison.[340]

There were three health-led interventions introduced by the Irish Prison Service during the Covid-19 pandemic: cocooning, quarantine and isolation.

‘Cocooning’ in prison

In line with public health guidance, the Irish Prison Service established a ‘cocooning’ regime for prisoners aged 70+ and for those who were deemed medically vulnerable to the virus. Other identified vulnerable groups of prisoners included those with: cancer, severe respiratory diseases such as severe COPD, rare diseases and pregnant women with cardiovascular diseases. Cocooned prisoners were removed from free association but could associate with each other in specific areas.

The practice of cocooning in prisons started on 25 March 2020 and ceased at the end of June 2020 (in line with the easing of public health restrictions), with the exception of a small number who were removed from this regime by early July 2020.[341] Prisoners who had been cocooning, and who were concerned about the virus, could request to be placed on a restricted regime.[342]

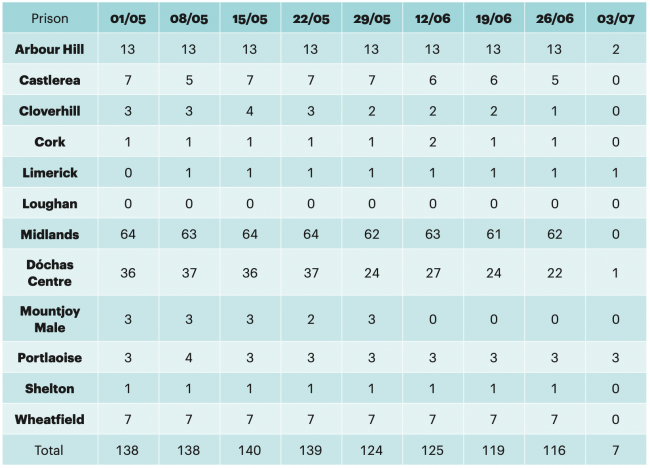

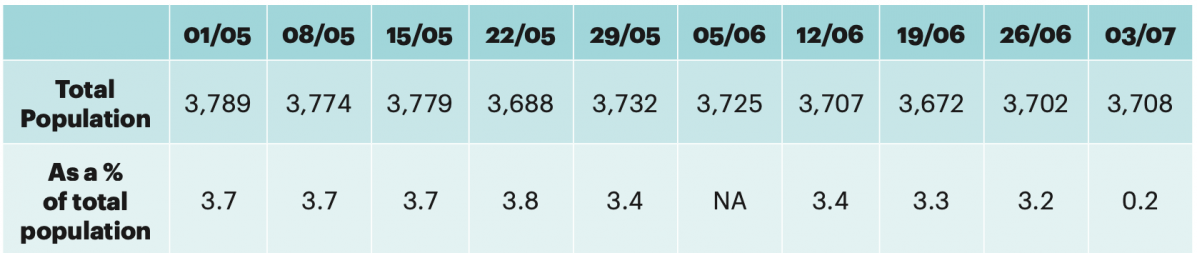

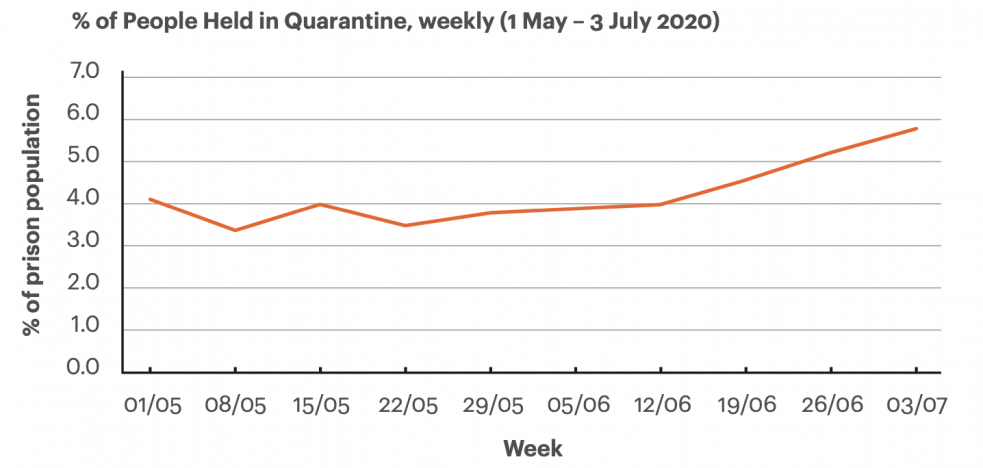

Approximately 3-4% of the total prison population were ‘cocooning’ on a weekly basis with the highest number of prisoners cocooning in Midlands, Dóchas, and Arbour Hill prisons. These populations are likely to have included people more vulnerable to the disease, such as the elderly, and pregnant women with cardiovascular diseases.343 At one point, the highest number of prisoners cocooning were women in the Dóchas Centre, comprising

52% of the prison population in that prison.[344] This reflects the high level of health needs among the female prison population.

Number of Prisoners ‘Cocooning’ (1 May to 3 July 2020):[345]

% of Prisoners Cocooning per week:[346]

Quarantining in Prison

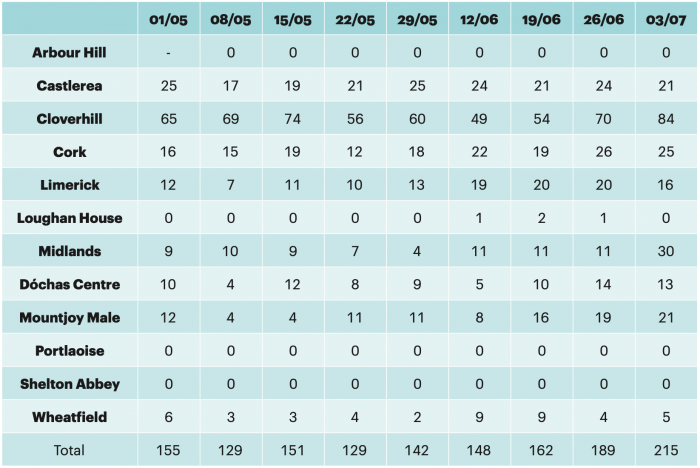

Quarantining is the practice of placing newly committed prisoners into confinement for 14 days before being transferred into the general population. Quarantine should be used only as medically necessary, and these procedures should result in living conditions clearly distinct from those found in solitary confinement.[347] The highest numbers quarantining, as would be expected, in the committal prisons: Cloverhill, Midlands, Cork and Mountjoy.

The purpose of this measure was to reduce the risk that a new committal who might potentially be incubating the virus could spread it to the general prison population.[348] Lengths of time in quarantine were dependent on the return of tests, which at the height of the pandemic took 10-14 days. This has been reduced in line with waiting times in the community, with a turnaround time of 24 to 36 hours.[349] The table below outlines the number of people quarantining in prisons from May to July 2020:[350]

Those either cocooning or in quarantine had access to services and activities including psychological supports, phone calls, television, tuck shop and chaplaincy services. Family contact was also increased through the provision of telephone services and video visits. However, these categories of prisoners were typically served meals in their cells and had access to one hour out of cell time, either on their own or with another prisoner depending on their status. Conditions varied across the prison estate, for example, quarantined prisoners in Loughan House were issued with a mobile phone.[351]

During the initial lockdown period, prisoners who were in medical isolation were on a more restrictive regime while testing was being completed. Prisoners in medical isolation did not have access to outdoor exercise.[352]

In the weeks between May and July 2020, 0.2% to 0.8% of the prison population were isolating, with a peak in numbers self-isolating (27) in the third week of May.[353] A dedicated isolation unit was created in Cloverhill Prison for a confirmed case among the prisoner population; this unit is currently being used to accommodate symptomatic prisoners who are suspected of having Covid-19. Prisoners continue to be isolated in this unit until cleared from isolation through the Covid-19 testing process.[354]

While the practices of ‘cocooning’, ‘quarantining’ and ‘isolation’ all formed part of the prison service’s response to the serious risk that Covid-19 presents to the physical health of the prison population, the practices share similarities with general restricted regimes. Therefore, oversight of the ongoing use of these practices, including regular review and tests for proportionality, is important.

Covid-19 Implications on General Health

Covid-19 is likely to have resulted in increased delays in accessing external medical appointments by the prison population. In 2018, 54 external medical appointments were recorded as missed in the Midlands Prison in 2018.[355] This information came to light in an investigation report that highlighted serious concerns regarding the delayed transfer of a terminally-ill man in prison to hospital to receive urgent medical attention. Non-medical staff shortages were given as a reason for the delay in the man’s transfer to hospital. This was described as a “major failing” by the Inspector of Prisons[356], and it may have amounted to inhuman or degrading treatment.

People with disabilities

Significant issues faced by prisoners with disabilities were identified in research publishedby IPRT in 2020, including the inaccessibility of the prison environment, as well as information and communication inaccessibility.[357] The research highlighted concerns by prisoners, staff and people working in the criminal justice system about access to the healthcare service. This included its inability to address health inequalities; limited access to specialist services such as physiotherapy; and a lack of continuity of care between prison and the community, demonstrating the need for a more joined up healthcare approach.

IPRT welcomes that in 2019, the Irish Prison Service appointed a lead person to oversee the promotion of equality and diversity in the Service.[358] The Irish Prison Service must ensure that reasonable accommodations are in place to support equal access of prisoners with disabilities to all aspects of prison life, in line with the Public Sector Duty.[359] Otherwise, the prison environment is directly contributing to a diminished standard of health among prisoners with disabilities and further exacerbating existing impairments.[360]

Women’s health

In 2019, a new Women’s Health Taskforce was set up by the Department of Health.[361] The taskforce aims to improve women’s health outcomes

and their experiences of healthcare. This is an opportunity to develop a continuum of healthcare from community to prison and prison back to the community. It is worth emphasising that, in the initial stages of the pandemic, the highest number of prisoners designated as ‘cocooners’ in any prison were in the main female prison, the Dóchas Centre. This is Ireland’s second smallest closed prison, and a small proportion of the women detained are aged over 50. At one point, 52% of the population in Dóchas were cocooning.[362] It has been reported that 97% of the Dóchas Centre population require prescription medication.[363] This demonstrates the high levels of healthcare needs among this group.

Indicators for Standard:

Indicators for Standard 12

Indicator S12.1: Responsibility for prisoner healthcare is held by the Health Service Executive (HSE), with independent inspections by the Health Information and Quality Authority (HIQA).

Responsibility for healthcare in prisons continues to be governed by prison healthcare. There are no independent inspections carried out by the Health Information and Quality Authority.

Indicator S12.2: Publication of an annual report on prison medical services as recommended by the CPT.

There has been no annual report published on prison medical services.

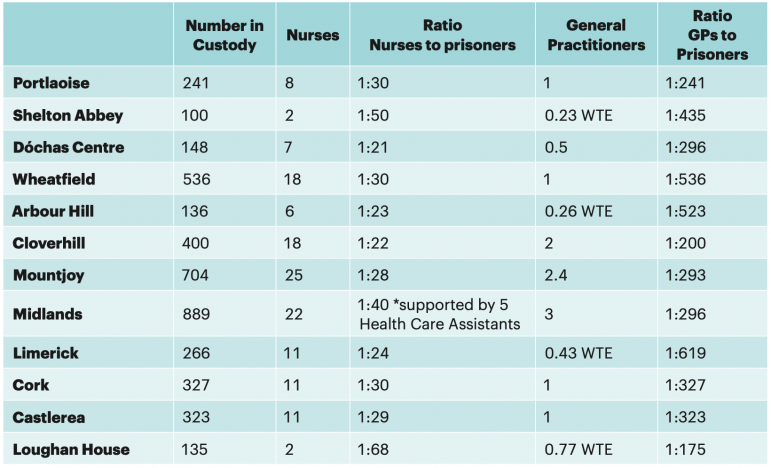

Indicator S12.3: Ratio of medical staff to prisoners, including GPs and nurses[364]

The number of GPs slightly increased in February 2020 from PIPS reporting in 2019, from 12[365] to 13.6[366] Whole Time Equivalent doctors, while there was an increase in the number of Whole Time Equivalent nurses from 127.5[367] to 141.[368]

Actions required:

Status of Standard 12: Progress

Rationale for Assessment

The Irish Prison Service is to be commended for keeping prisons Covid-free during the initial lockdown period of the pandemic. (See Part 1.) The prison healthcare needs assessment has commenced and is expected to be completed by the end of 2020. The ratios of medical staff to meet the needs of the prison population have improved, but are still too low to meet the healthcare needs of a population characterised by disproportionately poor health.[369]

Actions required

| Action 12.1: |

The prison Health Needs Assessment should be published by the end of 2020, and an action plan on its findings and recommendations developed and implemented. |

|---|---|

| Action 12.2: |

The Department of Justice and the Department of Health should oversee a joint strategy to provide a continuum of healthcare between prison health and public health. Transfer of responsibility for prison healthcare to the Department of Health should be considered. |

| Action 12.3: |

The Irish Prison Service and Prison Healthcare should ensure that reason- able accommodations for prisoners with disabilities are provided. Prisoners with disabilities should have full access to the medical and rehabilitative supports that they had prior to entering prison and upon return to the community. |

| Action 12.4: |

Healthcare interventions such as ‘cocooning’, ‘quarantining’, and ‘isolation’ should be subject to strict oversight and tested for proportionality by the Office of Inspector of Prisons. |

References:

-

330.

^

Kildare Street, Written answers Thursday 13 June 2019, Department of Justice and Equality, Prison Medical Service, https://www.kildarestreet.com/wrans/?id=2019-06-13a.296

-

331.

^

CPT/Inf (2011) 3 Report to the Government of Ireland on the Visit of Ireland carried out by the European Committee for the Prevention of Torture and Inhuman or Degrading Treatment or Punishment (CPT) from 25 January 2010 to 5 February 2010, https://rm.coe.int/1680696c98 and CPT/inf (2015) 38 Report to the Government of Ireland on the visit to Ireland carried out by the European Committee for the Prevention of Torture and Inhuman or Degrading Treatment or Punishment (CPT), https://rm.coe.int/pdf%20/1680727e23

-

332.

^

Inspector of Prisons, Healthcare in Irish Prisons Report by Judge Michael Reilly Inspector of Prisons November 2016, http://www.justice.ie/en/JELR/Healthcare_in_Irish_Prisons_Report.pdf/Files/Healthcare_in_Irish_Prisons_Report.pdf

-

333.

^

Irish Prison Service, Irish Prison Service response to requests for PIPS 2020 07.08.2020

-

334.

^

Ibid.

-

335.

^

Department of Justice, Information regarding the Justice Sector Covid-19 plans, http://www.justice.ie/en/JELR/Pages/Information_regarding_the_Justice_Sector_COVID-19_plans

-

336.

^

Department of Health, NPHET COVID-19 Sub-Group- Vulnerable People Membership, https://www.gov.ie/en/collection/301f5e-the-national-public-health-emergency-team-nphet-subgroup-vulnerable-/#nphetcovid-19-subgroup-vulnerable-people-membership

-

337.

^

Irish Prison Service, Irish Prison Service submits paper on best practice for Contact Tracing to World Health Organisation, https://www.irishprisons.ie/irish-prison-service-submits-best-practice-paper-world-health-organisation/ and see Clarke M, Devlin J, Conroy E, Kelly E, Sturup-Toft S. (2020) and Establishing prison-led contact tracing to prevent outbreaks of COVID-19 in prisons in Ireland, Journal of Public Health, https://academic.oup.com/jpubhealth/article/doi/10.1093/pubmed/fdaa092/5860 596?guestAccessKey=1cf37da2-ee58-452a-bccb-b72d39ac68f0

-

338.

^

Irish Prison Service, Irish Prison Service response to requests for PIPS 2020 07.08.2020

-

339.

^

Breaking News, First prisoner tests positive for Covid-19 https://www.breakingnews.ie/ireland/first-irish-prisoner-tests-positive-for-covid-19-1014738.html

-

340.

^

The Irish Examiner, Prison system reports second case of Covid-19, https://www.irishexaminer.com/news/arid-40039571.html, Covid-19 outbreak at Midlands Prison in Portlaoise, RTE News, https://www.rte.ie/news/coronavirus/2020/1030/1174982-covidmidlands-prison/, Irish Prison Service, Prisoner test positive for Covid-19 Limerick Prison, https://www.irishprisons.ie/prisonertest-positive-covid-19-limerick-prison/

-

341.

^

Irish Prison Service, Irish Prison Service response to requests for PIPS 2020 07.08.2020

-

342.

^

Kildare Street, Written answers, Tuesday, 14th July 2020, Department of Justice and Equality, Prisoner Data, https://www.kildarestreet.com/wrans/?id=2020-07-14a.2592

-

343.

^

Department of Justice, Information regarding the Justice Sector COVID-19 plans, 7th August 2020, http://www.justice.ie/en/JELR/Pages/Information_regarding_the_Justice_Sector_COVID-19_plans

-

344.

^

Irish Prison Service, Irish Prison Service response to requests for PIPS 2020 07.08.2020

-

345.

^

The Irish Prison Service has stated that figures have not been available for the 5 June due to an update on the Prison Information Management System. See Houses of the Oireachtas, Prisoner Data, Tuesday 14 July 2020 see ‘Covid-19 Data’, https://www.oireachtas.ie/en/debates/question/2020-07-14/945/

-

346.

^

Ibid.

-

347.

^

Amend (2020), The Ethical Use of Medical Isolation-Not Solitary Confinement-to reduce Covid-19 Transmission in Correctional Settings, https://amend.us/wp-content/uploads/2020/04/Medical-Isolation-vs-Solitary_Amend.pdf

-

348.

^

Kildare Street, Written answers, Tuesday, 14th July 2020, Department of Justice and Equality, Prisoner Data, https://www.kildarestreet.com/wrans/?id=2020-07-14a.2592

-

349.

^

Irish Prison Service, Irish Prison Service response to requests for PIPS 2020 07.08.2020.

-

350.

^

Houses of the Oireachtas, Prisoner Data, 14 July 2020, see ‘Covid-19 Data’, https://www.oireachtas.ie/en/debates/ question/2020-07-14/945/. The Irish Prison Service has stated that figures have not been available for the 5 June due to an update on the Prison Information Management System.

-

351.

^

Irish Prison Service, Irish Prison Service response to requests for PIPS 2020 07.08.2020

-

352.

^

Ibid.

-

353.

^

Houses of the Oireachtas, Prisoner Data, Tuesday 14 July 2020, https://www.oireachtas.ie/en/debates/question/2020-07-14/945

-

354.

^

Parliamentary Question 116 in Oireachtas COVID-19 Queries for answer by 11 May 2020, http://www.justice.ie/en/JELR/Queries-for-11-May-2020.pdf/Files/Queries-for-11-May-2020.pdf

-

355.

^

Office of the Inspector of Prisons Death in Custody Investigation Report Mr. I 2018, http://www.justice.ie/en/JELR/Pages/Office_of_the_Inspector_of%20Prisons_Death_in_Custody_Investigation_Report-Mr_I_2018

-

356.

^

Ibid.

-

357.

^

IPRT (2020) Making Rights Real for People with Disabilities in Prison, https://www.iprt.ie/site/assets/files/6565/people_with_disabilities_in_detention_-_single-pages.pdf

-

358.

^

IPS response to IPRT Data Clarifications for PIPS 2020, 18 August 2020

-

359.

^

Section 42 of the Irish Human Rights and Equality Commission Act 2014, http://www.irishstatutebook.ie/eli/2014/act/25/section/42/enacted/en/html

-

360.

^

IPRT (2020) Making Rights Real for People with Disabilities in Prison, https://www.iprt.ie/site/assets/files/6565/people_with_disabilities_in_detention_-_single-pages.pdf

-

361.

^

Government of Ireland, Women’s Health Taskforce, https://www.gov.ie/en/campaigns/-womens-health/

-

362.

^

Irish Prison Service, Irish Prison Service response to requests for PIPS 2020 07.08.2020

-

363.

^

The Irish Independent, Two prisons will spend €1.9 million for drug service, https://www.independent.ie/irish-news/crime/two-prisons-will-spend-19m-for-drug-service-39672479.html

-

364.

^

Houses of the Oireachtas, Prison Staff, Tuesday 7th July 2020, https://www.oireachtas.ie/en/debates/question/2020-07-07/651/

-

365.

^

Kildare Street, Written Answers Thursday 13 June 2019, Department of Justice and Equality, Prison Medical Service, https://www.kildarestreet.com/wrans/?id=2019-06-13a.296

-

366.

^

Houses of the Oireachtas, Prison Staff, Tuesday 7th July 2020, https://www.oireachtas.ie/en/debates/question/2020-07-07/651/

-

367.

^

Kildare Street, Written Answers Thursday 13 June 2019, Department of Justice and Equality, Prison Medical Service, https://www.kildarestreet.com/wrans/?id=2019-06-13a.296

-

368.

^

Houses of the Oireachtas, Prison Staff, Tuesday 7th July 2020, https://www.oireachtas.ie/en/debates/question/2020-07-07/651

-

369.

^

House of Commons, Health and Social Care Committee, Prison Health, p.10 https://publications.parliament.uk/pa/cm201719/cmselect/cmhealth/963/963.pdf