Standard 1: Towards a progressive penal policy (2020)

Standard 1:

Penal policy is continually monitored, implemented, evaluated and evolving.

Rationale:

Penal policy in Ireland should reflect the guiding principles and values of penal reform.At the same time, policy should maintain a level of flexibility to adapt to emerging issues, the needs of the prison population and the changing penal environment. Therefore, implementation, regular review and evaluation of penal policy are imperative.

Current context:

Publication of reports by the Implementation Oversight Group, which was set up to monitor progress on recommendations of the Penal Policy Review Group, has stalled.[127] The most recent report published was in February 2019, evidence that this substantial delay preceded the Covid-19 pandemic.

In the letter that accompanied the seventh progress report, the Chairperson stated that:

“The Group will review the overall implementation process to date and assess possible ways forward to ensure the promise of the Penal Policy Review Group’s vision is fulfilled.” [128]

In September 2020, the Minister for Justice outlined penal reform as a priority issue.[129] The Minister stated that a review is underway to examine

the progress made since the establishment of the Penal Policy Review Group and its 43 recommendations.[130] The recommendations made by the Joint Committee on Justice and Equality in its report on Penal Reform and Sentencing will also be examined.[131] This review, alongside the eighth progress report of the Implementation Oversight Group, is expected to be published by the end of 2020.[132]

One of the core recommendations made by the Penal Policy Review Group[133] was to establish Consultative Council to advise on penal policy. A commitment to establish the Consultative Council is contained in the 2020 Programme for Government - Our Shared Future.[134] The Consultative Council is intended to provide a forum for consultation with various external experts in penal policy and provide oversight in the implementation of penal policy commitments. It could also play an important role in refuting reactive legislative and policy proposals that are not grounded in evidence. The Consultative Council is one mechanism through which the vision of the Penal Policy Review Group can be progressed.

A number of other progressive policy and legislative commitments related to penal reform are outlined in the 2020 Programme for Government,[135] including:

• Ratify and implement the Optional Protocol to the Convention against Torture within 18 months of the formation of the Government.

• Establish a high-level cross-departmental and cross-agency taskforce to consider the mental health and addiction challenges of those imprisoned and primary care support on release.

• Review the existing functions, powers, appointment procedures and reporting processes for prison visiting committees.

• Review the Criminal Justice (Spent Convictions and Certain Disclosures) Act 2016 to broaden the range of convictions that are considered spent.

• Work with all criminal justice agencies to build capacity to deliver restorative justice, safely and effectively.

IPRT has welcomed and endorsed all of these commitments.[136]

Further positive developments in the area of policy include the delivery and publication of commissioned research by the Department of Justice as part of its Data and Research Strategy 2018-2020.[137] In particular, IPRT welcomes the publication of An Evidence Review of Recidivism and Policy Responses.[138] The review demonstrates that community sanctions are more effective than short-term prison sentences in reducing re- offending. It also identifies ‘dynamic’ (i.e. where intervention is possible) risk factors associated with recidivism such as unemployment and substance misuse. The importance of procedural fairness is also highlighted, whereby if people in conflict with the law believe they have been treated fairly, the likelihood of reoffending may be reduced:

“The evidence suggests that prisoners behave better when they feel that they are being listened to; treated respectfully and courteously; given an opportunity to state their view; and subjected to equitable rule enforcement. If this improved behaviour continues in the community it is to everyone’s benefit.”[139]

The research found that procedural unfairness communicates disrespect leading to further alienation, resistance and noncompliance. Early release programmes were also found to reduce reoffending; this was linked with trust. The findings of An Evidence Review of Recidivism and Policy Responses should form an important basis for future policy development.

An Evidence Review of Confidence in Criminal Justice Systems was also commissioned by the Department of Justice.[140] This identified a number of interventions to improve confidence in the criminal justice system. The review similarly identified the importance of applying procedural justice principles, along with the development of strategies to improve community policing and the use of restorative justice.

The Department of Justice also published a literature review that identified best practices in relation to victims’ interaction with the criminal justice system, including: the need for effective communication and information sharing, victim- centred responses, clearly-defined victim participation schemes, tailored approaches for victims with specialist needs (such as victims of sexual violence), and equal access and enforcement of rights.[141]

All of the above reviews will support evidence-led policymaking in the criminal justice system in Ireland. However, further investment is needed to provide an evidence-based research infrastructure. As identified by one of the leading Professors of Criminology in Ireland:

“Those of us with an interest in criminology and criminal justice in Ireland — mine stretches back more than 30 years at this stage — have long been frustrated by the lack of research infrastructure, reliable data and expert analysis. This has adversely impacted the quality of the debate about crime and punishment and puts us at a great disadvantage when it comes to, first, deciding how to respond and, secondly, deciding whether any response has had the desired effect.”[142]

These reviews should set the context for larger pieces of independent, empirical research, which should be properly funded by the State. During 2020, the Department of Justice undertook consultations on its first Criminal Justice Sectoral Strategy with various stakeholders including non- governmental organisations.[143] This wider external engagement in agenda setting is something PIPS has previously called for.[144]

The publication of the Draft Youth Justice Strategy in May 2020 is also promising, in particular proposals for diversion programmes for 18-24 year olds.[145] Evidence shows that the right interventions at the right points in time can lead to a reduction in offending rates among young adults.[146] The Programme for Government also commits to examining the potential to increase the age limit for the Garda Youth Diversion Programme to 24 years.[147]

Finally, at the outset of the Covid-19 pandemic, the Irish Prison Service and the Department of Justice adapted their penal policy approach through granting temporary release to low risk prisoners assessed on a case-by-case basis.[148] This positive action shows how the system could adapt, respond, and evolve during an emergency, and should be both maintained and extended. (See Standard 2, Imprisonment as a last resort).

Indicators for Standard:

Indicators for Standard 1

Indicator S1.1: Establishment of a Consultative Council

The first meeting of the Consultative Council has yet to take place. However, IPRT welcomes the renewed commitment to establish a Consultative Council in the 2020 Programme for Government – Our Shared Future.[149] The Minister for Justice has stated, “officials within my Department are expected to have concluded an examination of how best to take the commitment forward by the end of this year.”[150]

Indicator S1.2: Number of Penal Policy Review Group (PPRG) recommendations that have been fully implemented

There have been no Implementation Oversight Group reports published by the Minister for Justice to assess progress on recommendations made

by the Penal Policy Review Group since February 2019.[151] The Minister has stated that a review is underway to examine progress, and this will be accompanied by the eighth Implementation Report published before the end of 2020.[152]

Indicator S1.3: Number of recommendations of Joint Committee on Justice, Defence and Equality (2013) Report on Penal Reform that have been implemented

There have been no substantive progressive developments in relation to the five key recommendations made by the Joint Committee on Justice, Defence and Equality, and there has been significant regress on its recommendation to decarcerate:

1. Reduce the prison population by one-third over ten years:

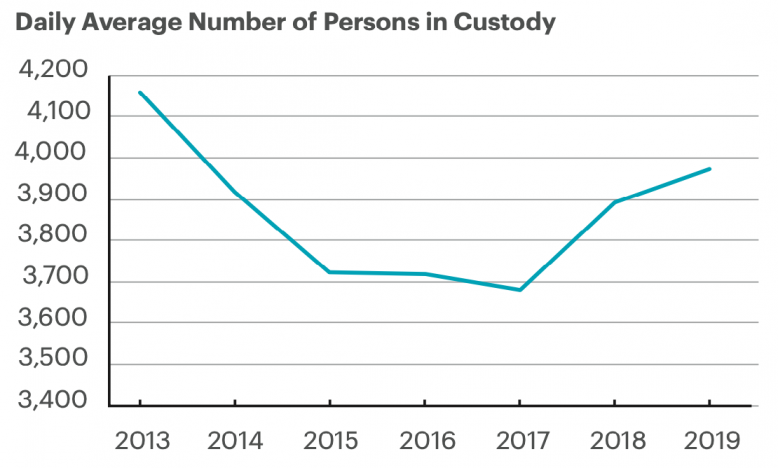

There continues to be an upward annual trend on the daily average number of persons in custody since 2017.

2. Commute sentences of less than six months for non-violent offences: no change

3. Increase remission to 33% for all sentences over one month and establish an enhanced remission scheme up to half sentence: no change

4. Introduce a single piece of legislation that would form the basis of a structured release system: no change

5. Address overcrowding and prison conditions with increased use of open prisons: while overcrowding was reduced during the Covid-19 pandemic (see Thematic Area 2: Prison Conditions and Regimes), there has been no long-term policy change in addressing this issue. The use of open prisons remains static.

Indicator S1.4: Number of recommendations of the Joint Committee on Justice and Equality (2018) Report on Penal Reform and Sentencing[153] that have been implemented.

Out of 29 recommendations made by the Joint Committee on Justice and Equality, many remain outstanding, including: the phasing out of solitary confinement, the capping of prison numbers, an accommodation policy of one person per cell and the establishment of an independent complaints system. (Some of these areas are further examined under the relevant standards in this report.) The Minister for Justice has stated that progress on recommendations by the Joint Committee on Justice and Equality will be included in the review underway on progress made on penal reform.[154]

Indicator S1.5: Publication of relevant data and research to inform evidence-led criminal justice policy

Three research reviews were commissioned and published by the Department of Justice over 2019/2020 including: An Evidence Review of Recidivism and Policy Responses[155], An Evidence Review of Confidence in Criminal Justice Systems[156] and Exploring Victims’ Interactions with the Criminal Justice System: A Literature Review.[157]

The Draft Youth Justice Strategy published by the Department of Justice in 2020 takes an evidence- led approach.[158] IPRT welcomes this evidence- based policy direction, along with the open public consultation processes on a number of strategies during 2020.[159]

Indicator S1.6: Adoption and implementation of PIPS standards

There has been no formal adoption and implementation of PIPS standards by criminal justice bodies. However, IPRT welcomes that the PIPS standards are taken into account in the Office of the Inspector of Prisons new inspection framework, A Framework for the Inspection of Prisons in Ireland.[160]

Progressive Practice:

Emerging Practice: Restorative Practice in Penal Policy

In 2018, the Council of Europe published a recommendation encouraging member States to use restorative justice[161]. 2019 saw the wider application of restorative justice in the practices of the Probation Service, which co-hosted a National Symposium on ‘Implementing Restorative Justice in Law, Policy and Practice’ with the Centre for Crime, Justice and Victim Studies in the University of Limerick in November 2019.[162] Restorative justice has also been included in the Victims Charter[163] and other relevant reviews.[164]

A commitment to restorative justice is also included in the Programme for Government[165], the Action Plan for the Joint Management of Offenders[166], and as part of the Office of Inspector of Prisons Framework for the Inspections of Prisons in Ireland[167], for prison staff to use restorative justice principles to prevent and resolve conflicts. The use of restorative practice was also recommended in prisons during the Covid-19 pandemic:

“Restorative practices could be used to give prisoners and staff a meaningful opportunity to express themselves and play a role in determining what should happen in relation to protocols for visits, relaxing regimes, and the provision of ongoing support.” [168]

Actions required:

Status of Standard 1: Progress

Rationale for Assessment

There has been very little reported progress on the implementation of penal policy recommendations and reforms over 2019/2020. This lack of progress in penal policy occurred prior to the Covid-19 pandemic. However, much progress is evident in other areas including the publication of research to inform evidence-based policymaking in Ireland. Nevertheless, a better research infrastructure to drive and inform policy-making is needed. The commitment to establish the Consultative Council and other penal reform commitments included in the 2020 Programme for Government are welcome. There was also swift, adapted policymaking evident in reducing the prison population by the Irish Prison Service and the Department of Justice at the outset of the pandemic.

| Action 1.1: |

The Department of Justice and Equality should publish the terms of reference, including the budget and powers of the Consultative Council. Following this, a date must be set for the Consultative Council’s initial meeting to advise on issues related to penal policy. [Repeated] |

|---|---|

| Action 1.2: |

The Department of Justice and Equality should publish its review of penal policy implementation within its committed timeline of end 2020. |

References:

-

127.

^

Seventh Report of the Implementation Oversight Group to the Minister for Justice and Equality - February 2019, http://www.justice.ie/en/JELz/IOG_Seventh_Report_of_the_Implementation_Oversight_Group_to_the_Minister_for_Justice_and_Equality.pdf/File/IOG_Seventh_Report_of_the_Implementation_Oversight_Group_to_the_Minister_for_Justice_and_Equality.pdf

-

128.

^

Letter from Chairperson of the Implementation Oversight Group to the Minister for Justice and Equality - February 2019, http://www.justice.ie/en/JELR/Pages/Penal_Policy_Review

-

129.

^

Kildare Street.com, Written Answers, Wednesday 23rd September 2020, Department of Justice and Equality, Penal Policy Review Group, https://www.kildarestreet.com/wrans/?id=2020-09-23a.437

-

130.

^

Strategic Review of Penal Policy, Final Report, http://www.justice.ie/en/JELR/Strategic%20Review%20of%20Penal%20Policy.pdf/ Files/Strategic%20Review%20of%20Penal%20Policy.pdf

-

131.

^

Joint Committee on Justice and Equality (2018) Report on Penal Reform and Sentencing, https://data.oireachtas.ie/ie/oireachtas/committee/dail/32/joint_committee_on_justice_and_equality/reports/2018/2018-05-10_ report-on-penal-reform-and-sentencing_en.pdf

-

132.

^

Kildare Street, Department of Justice and Equality, Penal Policy Review Group, https://www.kildarestreet.com/wrans/?id=2020-09-23a.437

-

133.

^

See Recommendation 42 of the Strategic Review of Penal Policy, http://www.justice.ie/en/JELR/Strategic%20Review%20of%20 Penal%20Policy.pdf/Files/Strategic%20Review%20of%20Penal%20Policy.pdf

-

134.

^

The Green Party, Programme for Government - Our Shared Future, https://www.greenparty.ie/wp-content/uploads/2020/06/ProgrammeforGovernment_June2020_Final.pdf

-

135.

^

Ibid, p.86

-

136.

^

See IPRT’s 5 Key Recommendations for the Programme for Government 2020+, https://www.iprt.ie/elections-2020/5-keyrecommendations-for-the-programme-for-government-2020/ and in relation to reform of prison visiting committees, see Action 24.3 of Progress in the Penal System (PIPS): A Framework for Penal Reform (2019), https://pips.iprt.ie/progress-in-the-penal-system-pips/part-2-measuring-progress-against-the-standards/d-complaintsaccountability-and-inspections-mechanisms/24-inspections-and-monitoring/

-

137.

^

Department of Justice and Equality, Data & Research Strategy 2018-2020 Supporting delivery of “A safe, fair and inclusive Ireland”, http://www.justice.ie/en/JELR/Department_of_Justice_and_Equality_Data_and_Research%20_Strategy_2018-2021.pdf/Files/Department_of_Justice_and_Equality_Data_and_Research%20_Strategy_2018-2021.pdf

-

138.

^

O’Donnell I. (2020) An Evidence Review of Recidivism and Policy Responses, http://www.justice.ie/en/JELR/An_Evidence_Review_ of_Recidivism_and_Policy_Responses.pdf/Files/An_Evidence_Review_of_Recidivism_and_Policy_Responses.pdf

-

139.

^

Ibid, p.91.

-

140.

^

Hamilton C. & L. Black (2019) An Evidence Review of Confidence in Criminal Justice Systems, http://www.justice.ie/en/JELR/An_Evidence_Review_of_Confidence_in_Criminal_Justice_Systems_(2019).pdf/Files/An_Evidence_ Review_of_Confidence_in_Criminal_Justice_Systems_(2019).pdf

-

141.

^

Healy D. (2019) Exploring Victims’ Interactions with the Criminal Justice System: A Literature Review, http://www.justice.ie/en/ JELR/Victim_Interactions_with_the_Criminal_Justice_System.pdf/Files/Victim_Interactions_with_the_Criminal_Justice_System.pdf

-

142.

^

O’Donnell I. (2020) Reducing Reoffending: Choices and Challenges*, Irish Probation Journal, Volume 17, p.9 October 2020

-

143.

^

Department of Justice, Criminal Justice Sectoral Strategy, https://www.gov.ie/en/consultation/d8def-criminal-justice-sectoral-strategy-public-consultation/

-

144.

^

See Action 1.2 of Progress in the Penal System (2019): A Framework for Penal Reform, https://pips.iprt.ie/progress-in-the-penal-system-pips/part-2-measuring-progress-against-the-standards/a-an-effective-andhumane-penal-system/1-towards-a-progressive-penal-policy/

-

145.

^

See Department of Justice, Draft Youth Justice Strategy 2020-2026, http://www.justice.ie/en/JELR/Draft_Youth_Justice_ Strategy_2020_(Public_Consultation).pdf/Files/Draft_Youth_Justice_Strategy_2020_(Public_Consultation).pdf

-

146.

^

IPRT (2015) Turnaround Youth: Young Adults (18-24) in the Criminal Justice System: The case for a distinct approach, https://www.iprt.ie/site/assets/files/6357/iprt-turnaround-web-optimised.pdf

-

147.

^

The Green Party, Programme for Government - Our Shared Future, https://www.greenparty.ie/wp-content/uploads/2020/06/ProgrammeforGovernment_June2020_Final.pdf

-

148.

^

Department of Justice and Equality, Covid-19 Information regarding the Justice Sector Covid-19 plans, http://www.justice.ie/en/JELR/Pages/Information_regarding_the_Justice_Sector_COVID-19_plans

-

149.

^

The Green Party, Programme for Government - Our Shared Future, https://www.greenparty.ie/wp-content/uploads/2020/06/ProgrammeforGovernment_June2020_Final.pdf

-

150.

^

Kildare Street, Written answers, Thursday, 15 October 2020, Department of Justice and Equality, Penal Policy Review Group, https://www.kildarestreet.com/wrans/?id=2020-10-15a.683

-

151.

^

Department of Justice and Equality, Penal Policy Review, http://justice.ie/en/JELR/Pages/Penal_Policy_Review

-

152.

^

Kildare Street, Written answers, Wednesday, 23 September 2020, Department of Justice and Equality, Penal Policy Review Group, https://www.kildarestreet.com/wrans/?id=2020-09-23a.437

-

153.

^

Houses of the Oireachtas (2018), Joint Committee on Justice and Equality, Report on Penal Reform and Sentencing, https://data.oireachtas.ie/ie/oireachtas/committee/dail/32/joint_committee_on_justice_and_equality/reports/2018/2018-05-10_ report-on-penal-reform-and-sentencing_en.pdf

-

154.

^

Kildare Street, Written Answers, Wednesday 23 September 2020, Department of Justice and Equality, Penal Policy Review Group, https://www.kildarestreet.com/wrans/?id=2020-09-23a.437

-

155.

^

O’Donnell I. (2020) An Evidence Review of Recidivism and Policy Responses, http://www.justice.ie/en/JELR/An_Evidence_Review_ of_Recidivism_and_Policy_Responses.pdf/Files/An_Evidence_Review_of_Recidivism_and_Policy_Responses.pdf

-

156.

^

Hamilton C. & L. Black (2019) An Evidence Review of Confidence in Criminal Justice Systems, http://www.justice.ie/en/JELR/An_Evidence_Review_of_Confidence_in_Criminal_Justice_Systems_(2019).pdf/Files/An_Evidence_ Review_of_Confidence_in_Criminal_Justice_Systems_(2019).pdf

-

157.

^

Healy D. (2019) Exploring Victims’ Interactions with the Criminal Justice System: A Literature Review, http://www.justice.ie/en/ JELR/Victim_Interactions_with_the_Criminal_Justice_System.pdf/Files/Victim_Interactions_with_the_Criminal_Justice_System.pdf

-

158.

^

Department of Justice, Draft Youth Justice Strategy 2020-2026, http://www.justice.ie/en/JELR/Draft_Youth_Justice_ Strategy_2020_(Public_Consultation).pdf/Files/Draft_Youth_Justice_Strategy_2020_(Public_Consultation).pdf

-

159.

^

See Irish Penal Reform Trust submissions at www.iprt.ie/iprt-submissions

-

160.

^

Office of the Inspector of Prisons, A Framework for the Inspection of Prisons in Ireland, https://www.oip.ie/wp-content/uploads/2020/09/OIP-Inspection-Framework-Single.pdf

-

161.

^

Council of Europe, Recommendation CM/Rec (2018) 8 of the Committee of Ministers to member States concerning restorative justice in criminal matters, https://search.coe.int/cm/Pages/result_details.aspx?ObjectId=09000016808e35f3

-

162.

^

The Probation Service, Probation Service Annual Report 2019, p.14 https://www.gov.ie/en/publication/5ba4c-probation-service-annual-report-2019/

-

163.

^

Government of Ireland, Victims Charter, https://www.victimscharter.ie/wp-content/uploads/2020/04/Victims-Charter-22042020.pdf

-

164.

^

Department of Justice and Equality (2020) Supporting a Victim’s Journey, A plan to help victims and vulnerable witnesses in sexual violence cases, http://www.justice.ie/en/JELR/Supporting_a_Victims_Journey.pdf/Files/Supporting_a_Victims_Journey.pdf

-

165.

^

The Green Party, Programme for Government – Our Shared Future, https://www.greenparty.ie/wp-content/uploads/2020/06/ProgrammeforGovernment_June2020_Final.pdf

-

166.

^

Department of Justice, An Garda Síochána, The Probation Service and the Irish Prison Service, Action Plan for the Joint Management of Offenders, http://www.justice.ie/en/JELR/action-plan-for-the-joint-management-of-offenders.pdf/Files/actionplan-for-the-joint-management-of-offenders.pdf

-

167.

^

Office of the Inspector of Prisons (2020), A Framework for the Inspection of Prisons in Ireland, https://www.oip.ie/wp-content/ uploads/2020/09/OIP-Inspection-Framework-Single.pdf

-

168.

^

Ibid, p.6.