Current context:

Out-of-cell time with access to purposeful activity is central to the rehabilitation process. In 2020, the impact of Covid-19 restrictions within prisons have meant delays for prisoners progressing in the system. Due to reduced access to activities such as school and day programmes, the rehabilitative purpose of prison has deteriorated.

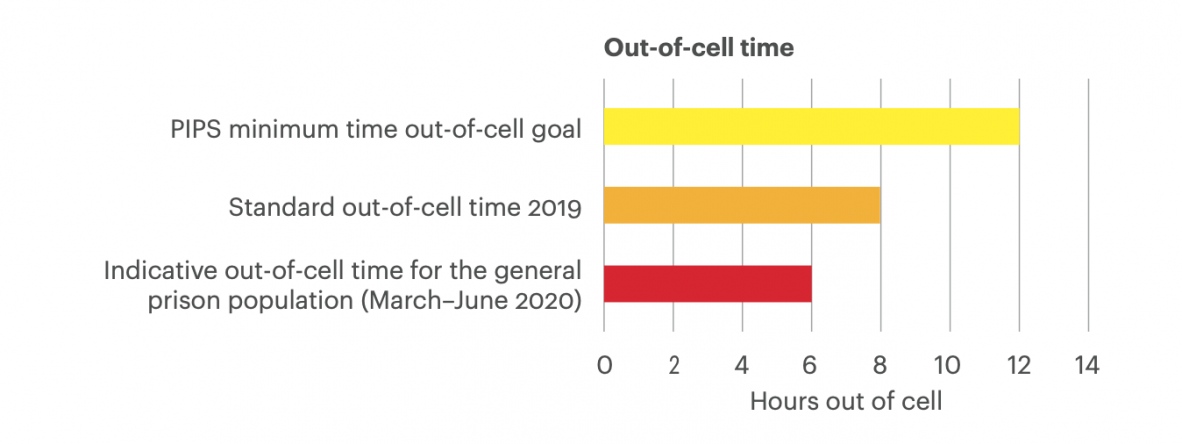

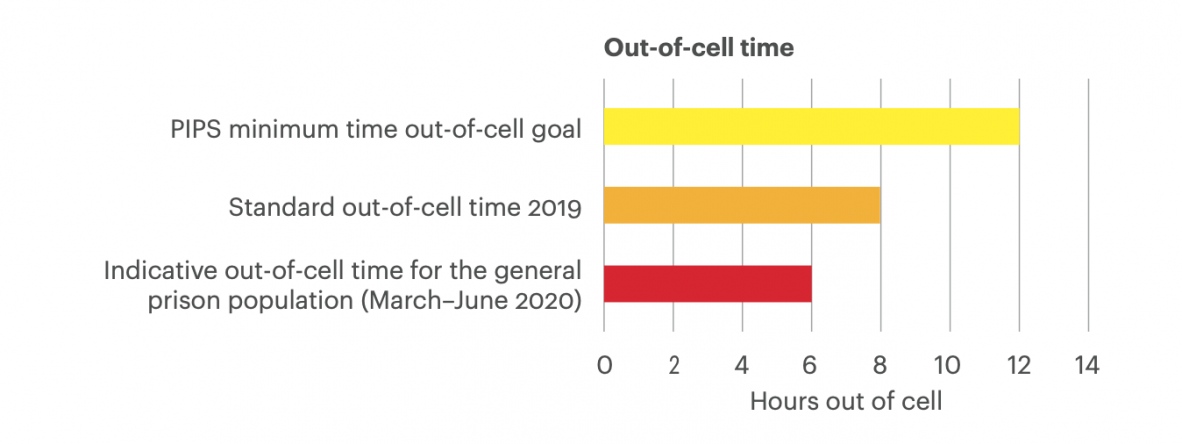

In 2020, despite being identified as an action in PIPS 2019,[280] there has been no regularly published information on the out-of-cell time available to people in prison.[281] Therefore it is not possible to assess whether there has been any progress on IPRT’s target that all prisoners should be receiving 12 hours out-of-cell time. However, it was reported that, prior to the pandemic, out of cell time had decreased by 32% from 11 hours and 10 minutes to 7 hours and 35 minutes in the main female women’s prison.[282]

The impact of limited out-of-cell time on prisoners was a recurrent theme in prison visiting committee reports published in 2020 for the year 2018.[283] The Mountjoy Prison Visiting Committee Annual Report described negative impact of limited out-of-cell time on mental health, in which some prisoners on restricted regimes developed “disrupted sleeping patterns.” The Committee also reported that some prisoners declined to leave their cells for the two hours guaranteed out-of-cell time (under the Prison Rules, 2007) and “may become disoriented and confused.”[284]

Prior to the pandemic, the most recent census by the Irish Prison Service shows that almost 15% of people in prison were on a restricted regime (i.e. with less than five hours daily out of cell time).[285] As a result of the Covid-19 pandemic, the number of prisoners on restricted regime increased by 30.8% from 589 in January 2020 to 770 in April 2020.[286]

Of the 770, 201 were restricted due to Covid-19 infection control measures. This increased by a further 8% in July 2020 to a total of 833 prisoners,[287] of whom 287 were restricted due to Covid-19 infection control measures.

While IPRT acknowledges that practices such as ‘cocooning’, ‘quarantining’, and ‘isolation’ (see Standard 12, Healthcare) were for medical reasons (Rule 103 of the Prison Rules)[288], the number of people in prison impacted by limited out-of-cell time during the Covid-19 pandemic period has been immense. Journals were provided to 88 people who were cocooning across seven prisons to capture their lived experiences.[289] The journals depicted harsh prison conditions, including severely limited access to daily yard time to allow for exercise and fresh air, as described by one prisoner below:[[footnote num=2]90]

“Yesterday, we were let out to the yard at approx. 10:30am [and] today we are out at 6:30pm. That is a long time to be left in a small cell. [..] 30 hrs in cell [is] very hard to do.” [291]

Prisoners described feeling like a ‘leper’ or a ‘pariah’ because of being spoken to through a closed door. The significant value of this journalling project extends beyond cocooning, and its findings and recommendations should be applied to conditions experienced by the 15% of the prison population who were held on restricted regimes pre-pandemic.

Snapshot figures (see Indicator S16.1) during the Covid-19 pandemic demonstrate that general out- of-cell time was severely limited. Prisoners from the general population in Dóchas, Cork and Castlerea were subject to similar periods of 19-hour lock-up, while Mountjoy Prison reported 19.5-hour lock up as a standard practice, meaning just 4.5 to 5 hours out of their cell every day.[292]

Movement of prisoners around prisons was severely restricted, with impacts on out-of-cell and yard time. Prison schools were closed from March to August 2020. Prison gym facilities for prisoners remained open, albeit on a reduced schedule.

New initiatives were developed to bring education into the cell, such as education modules for an in-cell TV channel, and other resources such as quizzes and mindfulness books.[293] However, more must be done to develop modes of interactive learning in prisons. This is more important given that class sizes have had to be reduced as a result of the pandemic, meaning prisoners have reduced hours access to the schools. Prior to the pandemic, participation rates varied across the prison estate, with Arbour Hill Prison highest at 71.4%, followed by Mountjoy Prison at 35.2%, Wheatfield at 38.3% and Castlerea at 39.2% in February 2020.[294] The overall education participation rate across the prison estate was 42.4% in February 2020.

Easing of Restrictions

In its follow-up statement issued in July 2020, the CPT emphasised that: “Importantly, temporary restrictions imposed to contain the spread of the virus must be lifted as soon as they are no longer required.”[295] This relates, in particular, to limitations on arrangements for detained persons to contact the outside world and reductions in the range of activities available to them.

It is important that any ongoing restrictions are proportionate, medically necessary, time-limited and relaxed when it is safe to do so. To this end, it is important that any plans to unwind restrictions are implemented as soon as it is safe to do so.

Indicators for Standard:

Indicators for Standard 16

Indicator: S16.1: Hours out-of-cell for all prisoners, including prisoners on a restricted regime.

IPRT requested figures on the number of people on all forms of restricted regimes for March – April 2020 at the beginning of Covid-19 restrictions. However, the Irish Prison Service only began to collate figures related to confinement status on 27 April 2020.[296]

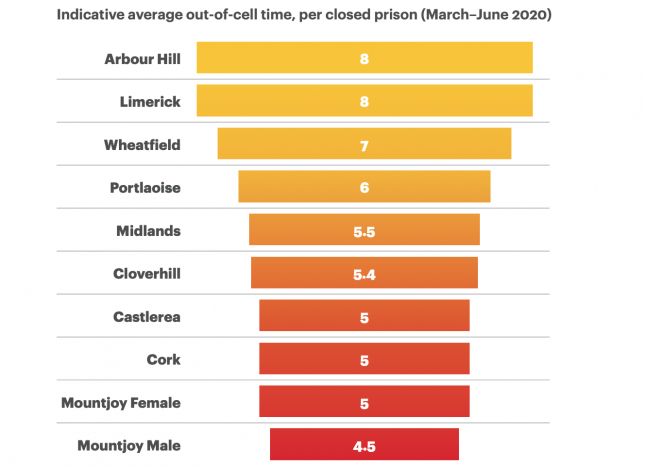

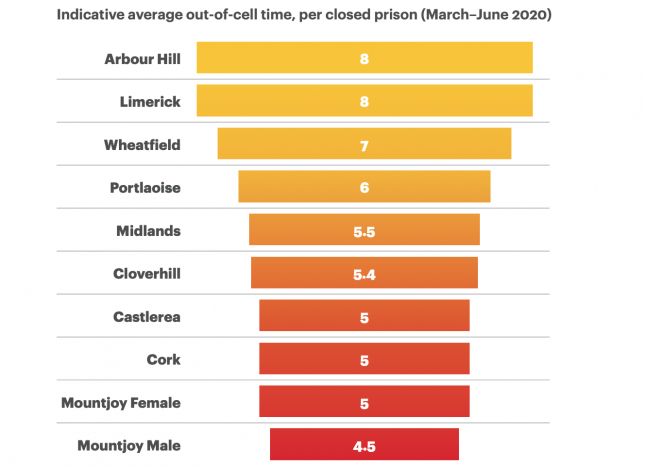

Outlined below is an indicative list of the average out-of-cell time broken down by each closed prison during the Covid-19 restrictions (12 March 2020 to 29 June 2020).[297]

As expected, out-of-cell time was reduced for the general prison population during the pandemic. However, this data is only a snapshot depiction. The Irish Prison Service did not collate data related to the length of time people were held in confinement during the beginning of the pandemic.[298] Further oversight is needed on the lengths of time people are being held in their cells. The Office of Inspector of Prisons and Maynooth University have recommended that prisons should keep track of the extent to which exercise and meaningful human contact are given to people who are subjected to any restricted regime.[299]