Current context:

PIPS 2019 reported that Ireland’s imprisonment rate in July 2019 was 82 per 100,000.[170] As of July 2020, Ireland’s imprisonment rate was 75 per 100,000.[171] This 7% reduction is attributed to the increased number of prison releases and a decrease in prison committals that occurred during the initial period of the Covid-19 pandemic,[172] and is not linked with long-term policy or sentencing reform.

Custodial sentences

Annual figures reveal a continual increase in prison population numbers in Ireland since 2017. There was a 2% increase in the daily average number of people in custody from 3,893 in 2018 to 3,971 in 2019.[173] There was again a significant increase in the number of people committed to prison for short sentences:[174]

- Those committed under sentence of less than 3 months increased by 75 or 12.1%, from 618 in 2018 to 693 in 2019.

- Those committed under sentence of 3 to less than 6 months increased by 116 or 7.8% from 1,491 in 2018 to 1,607 in 2019.

- Those committed under sentence of 6 to less than 12 months increased by 158 or 15.9% from 995 in 2018 to 1,153 in 2019.

There was a total of 3,453 committals on short sentences (excluding committals for fines default) in 2019. By comparison, 2,791 community service orders were carried out in the same year.[175]

In 2019, there was another decrease on numbers participating in early release programmes from prison, from 218 in 2018 to 206 in 2019.[176] Compliance rates for community return remain high at 89%. There has been a revision of the qualification time from 50% of total sentence to 50% of remitted sentence for eligible cases serving sentences of less than three years. However, the Irish Prison Service failed to meet its own target of 250 releases.[177] Planned and structured early release, including parole, for prisoners is important.

As highlighted by O’Donnell (2020):

“the act of placing trust in prisoners and holding them to their word leads to an improvement in behaviour.”[178]

2019 also saw the number of committals for the non-payment of court-ordered fines almost double from 455 in 2018 to 861 in 2019.[179] The operation of the Fines (Payment and Recovery) Act 2014[180] should be reviewed to inform further development and implementation of alternative sanctions to imprisonment.

Non-custodial sentences

Community sanctions must be accessible and available nationwide so that the judiciary has full confidence in applying these sanctions. The Probation Service plays an important role in providing the judiciary with pre-sanction and community service reports.[181] In 2019, an inter- agency group comprising key stakeholders across the justice sector was established to focus on improved effectiveness in the area of pre-sanction assessment reports. The group considered a broad range of issues and made proposals. These proposals should be published, to help inform the development and administration of community sanctions.[182]

During the Covid-19 pandemic, the Probation Service, like other criminal justice agencies adapted its way of working, including developing specific targeted responses for those at most risk of offending.[183] However, generally, there has been less information made publicly available on how the Probation Service and community sanctions have operated during the pandemic. During the initial lockdown, community service sites were closed for health and safety reasons. The Probation Service used telephone and video contact during this period.[184] Since then, as a result of Covid-19 restrictions such as social distancing, community service sites are operating but at reduced capacity.

In March 2020, 2,376 people were on a Community Service Order. In July 2020, there was a 26% decrease in the number of people on Community Service Orders at 1,747.[185] Over the same period, there was a 22% increase in the numbers on Community Return[186], i.e., prisoners returning to the community through a structured early release programme. Seventy-nine people were on Community Return in March 2020, with numbers rising every month, reaching 97 in July 2020.[187]

There will be a need for ongoing review of how community sanctions operate in the context of the pandemic, with a need for innovative solutions to avoid any potential negative impact on the prison population.

Need for analysis

Analysis is needed to examine why increasing numbers of short sentences continue to be handed down in the Courts, when legislation – the Criminal Justice (Community Service) Amendment Act 2011[188] – requires the court to first consider community service as an alternative. Such analysis should examine whether there have been ‘net widening effects’ (i.e. where community sanctions are being used for low-risk offenders who would otherwise have received lighter sanctions) in the criminal justice system, since a reduction in short- term prison sentences has not coincided with an increased use of community service orders. The analysis should also examine the effectiveness of community sanctions with a view to strengthening confidence in their operation across the country, in order to reduce the use of short-term custodial sentences. Where barriers to the use of community sanctions by the Courts are identified, these must be addressed. The proposed analysis should also examine the use of structured release programmes such as the Community Support Scheme and the Community Return Programme, with a view to enhancing and expanding successful programmes.

Sentencing Data and Guidelines

In 2020, a Sentencing Guidelines and Information Committee was established, as required by the Judicial Council Act 2019.[189] The functions of the Committee include: drafting and amending sentencing guidelines; monitoring the operation of sentencing guidelines; and collating information on sentences imposed by the courts. The systematic collation and publication of sentencing data will be important to inform policy and enhance public confidence in the justice system. However, it is important that the introduction of sentencing guidelines does not impact adversely on penal policy. In this respect, imprisonment as a sanction of last resort should be enshrined as a core sentencing principle, as previously recommended by the Penal Policy Review Group.[190]

The principle of imprisonment as a last resort is outlined in the 2020 Review of Suspended Sentences published by the Law Reform Commission:

“The basic premise of the principle of last resort is that a custodial sentence should not be imposed unless no other penalty or sanction would be sufficient to reflect the seriousness of the offending behaviour. The development of this principle has received much less attention in the Irish courts than other sentencing principles, such as proportionality. However, it has been suggested that the constitutional principle of proportionality implies that prison should only be used as a last resort. As all sentences must be proportionate to the gravity of the offence and the personal circumstances of the offender, it therefore follows that, in order for this principle to be observed, the most serious form of punishment available under Irish criminal law – the deprivation of personal liberty – should only be reserved for the most serious offending behaviour.[191]

The Commission recommended that part suspended sentences rank below a term of imprisonment and above the Community Service Order on the scale of severity and above a fully suspended sentence. It examined mitigating factors relevant to whether a sentence should be suspended. This included factors such as: illness/ physical/mental disability and family circumstances including pregnant women or women with dependent children.[192] The Commission recommended that these factors could be set out in a sentencing guideline by the Sentencing Guidelines and Information Committee.

IPRT recommends that the principle of parsimony in punishment (i.e., that the use of prison should be minimised, and that sentences should be no longer than absolutely necessary) should also inform the future development of sentencing guidelines. These proposed principles would counteract the potential risk of sentence inflation that, at least for some offences, may have been linked with the development of sentencing guidelines in other jurisdictions.[193]

Covid-19 Releases

During the Covid-19 pandemic, the categories of prisoner targeted by the Department of Justice and the Irish Prison Service for release were those serving sentences of less than 12 months for non- violent offences and those who had less than six months remaining to serve.[194]

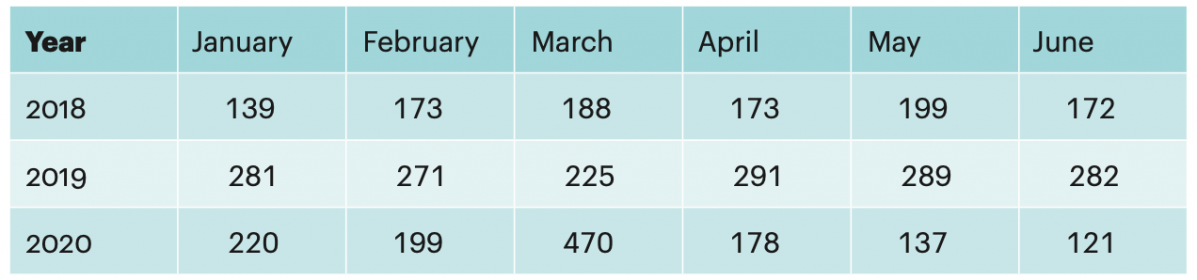

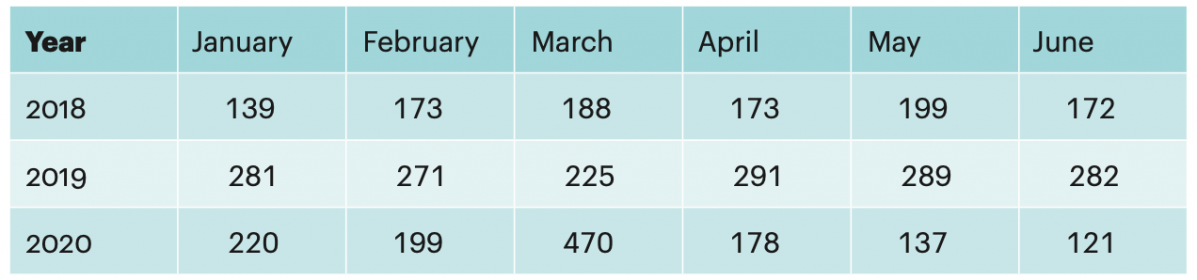

Full temporary releases 2018–2020[195]:

Temporary releases doubled in March 2020 (in response to the Covid-19 pandemic) compared to March 2019. Of the 470 people granted full temporary release in March 2020, 64% were serving a sentence of less than 12 months.[196] The number of temporary releases for females increased from 23 in March 2019 to 56 in March 2020. For males, temporary releases doubled from 202 to 414 in the same period.[197]

While these actions were necessary and strongly welcomed by IPRT, there may have been other prisoners who were suitable for release but who were excluded from the eligibility criteria. At the outset of the pandemic, and in line with calls from international human rights bodies, IPRT had called for the release of particularly vulnerable cohorts of prisoner, such as the elderly, subject to public safety risk assessment.[198] This was echoed by the Office of Inspector of Prisons and Maynooth University in July 2020:

“Criteria for release included the remaining length of sentence and whether the offence was violent in nature. However, there are still persons who could arguably be categorised as of a low risk to the community, but who were not considered for release within the existing criteria. The current circumstances provide an opportunity to review these early release criteria. We urge that mechanisms for early release and alternatives to custody are used to the widest extent.”[199]

For those prisoners who have remained in prison during the pandemic, the harmful effects of imprisonment were exacerbated through the imposition of Covid-19 restrictions, including: greater isolation from family and social networks, limited out-of-cell time, a lack of purposeful activity, with wider uncertainty of the situation including its impact on sentence management and reintegration.

Progressive Practice:

Progressive Practice: PASS

The extended Presumption Against Short Sentences (PASS) (from sentences of less than 3 months to 12 months) came into effect on 4 July 2019 in Scotland under the Presumption Against Short Periods of Imprisonment (Scotland) Order 2019.[200] The purpose of PASS is to give greater use to encouraging community sanctions.

Based on monitoring information published by the Scottish Government for the period of July 2019 to December 2019 (the first six months of the extended presumption), there is emerging evidence that the number of short custodial sentences has been reduced in Scotland.

- The number of community disposals reached their highest level in October 2019 (since April 2017) when 24% of disposals were community orders.

- Custodial disposals have been decreasing since April 2019 and reached a low in November/December 2019.

- The number of sentences of 12 months or less was estimated to be approximately 665 in November and December 2019

- (lowest since April 2017).

- The proportion of disposals accounted for by custodial sentences of 12 months or less had fallen from 12.8% in April 2019 to 9.5% in November 2019

While caution must be taken in accrediting changes in sentencing patterns directly to the extended presumption, short-term prison sentences of less than 12 months are decreasing in Scotland, which is a promising result.[201] However, caution must be taken to ensure that this does not lead to further net widening of people in the criminal justice system.

Emerging Evidence

An international review commissioned by the Department of Justice found growing evidence that community service and suspended sentences are more effective than short terms of imprisonment in terms of reducing re- offending,[202] among other positive outcomes. One study in the Netherlands showed that recidivism rates were 46.8% lower for those who completed community service compared with recidivism after imprisonment.[203] The review also found a lack of evidence to support the deterrence effect of short-term sentences.

IPRT’s research previously found a null effect in rates of re-arrest after serving a community service order and short prison sentence.[204] A comprehensive review of how community service is currently operating in Ireland should be undertaken in order to identify areas for improvement, and support public and judicial confidence in the efficacy of non-custodial sanctions.